HOW FOOD WORKS: Fall-Apart, Slow Roast Lamb

A comprehensive guide to deliver perfect slow cooked lamb to your table, every single time.

Hey friends!

Welcome to the first ever newsletter for ‘HOW FOOD WORKS’ - a weekly deep dive into all things food & science!

Since Valentine’s Day is upon us, I thought i’d start off by taking you through how I make my fool-proof slow-roast lamb - a perfect showstopper to impress a certain someone (or yourself!).

I want this newsletter to be of as much value as possible to you, (and in turn, to me!), so please feel free to leave a comment and get a discussion going! I’ve also created a chat for all of your questions and suggestions, and alternatively, you can contact me privately.

I am so excited to have finally started this journey, I can only say a humungous thank you for joining me!

Fiona :)

Slow-cooking meats is an ancient practice, used long before the invention of the ovens of today. There were no thermometers or timers or temperature settings and yet, people managed just fine. Don’t get me wrong, there is definitely a science to it, but I find it’s actually the over-complication that leads to the pitfalls. I have done lots and lots of testing to get you a comprehensive guide that arms you with the foundations, and I am pleased to tell you the results have showed that the best way, is the simple way.

The Breakdown:

I think information first starts to get murky when deciding on the technique to use. There are three terms which are frequently used interchangeably, and I think it causes understandable confusion.

Slow-roasting and roasting aren’t the same thing. Slow-roasting is categorised in the 95-150°C region, whereas roasting is in the 180-230°C region. We are focusing on slow-roasting because although you can obviously roast the lamb, this is a foolproof guide, and slow-roasting is much more foolproof.

The optimal internal temperature for a fall-apart slow-roast lamb is around 95°C. Since we can slow-roast in and around this region (95-110°C), this technique is a very good, low-risk choice.

- Temp vs. Time

‘But’ I hear you ask, ‘Higher temperature = Faster cooking. It just means we’ll get to optimal internal temperature quicker. That’s science’.

That it is. Higher temperatures would push you into roast lamb territory, a very valid method of cooking. However, this process of faster cooking at a higher heat is very different to the slow-roasting we’re talking about in this newsletter.

First off, when you cook at a high temperature, the outer layers cook much faster than the core. This leaves you with well-done meat on the outside and rarer meat on the inside. That still makes for a lovely table centrepiece, but it is definitely not as risk-averse. The lamb cooks faster, which is great, but it is also more easily overcooked, which is not so great. And, it produces a pretty different kind of dish. It’s more a lamb you would carve rather than seamlessly pull apart.

Second, the melt-in-the-mouth lamb texture we want is a result of collagen (connective tissues in the meat) breaking down into gelatin, slowly. By cooking low and slow, you’re giving your lamb more time to break down collagen into gelatin without running the risk of overcooking. If you overcook, you run the risk of the collagen instead shrinking, squeezing out moisture before it can turn to gelatin. This would leave you with dry, chewy meat instead of tender, juicy lamb.

Remember, this is what we want:

- Rest vs. No Rest

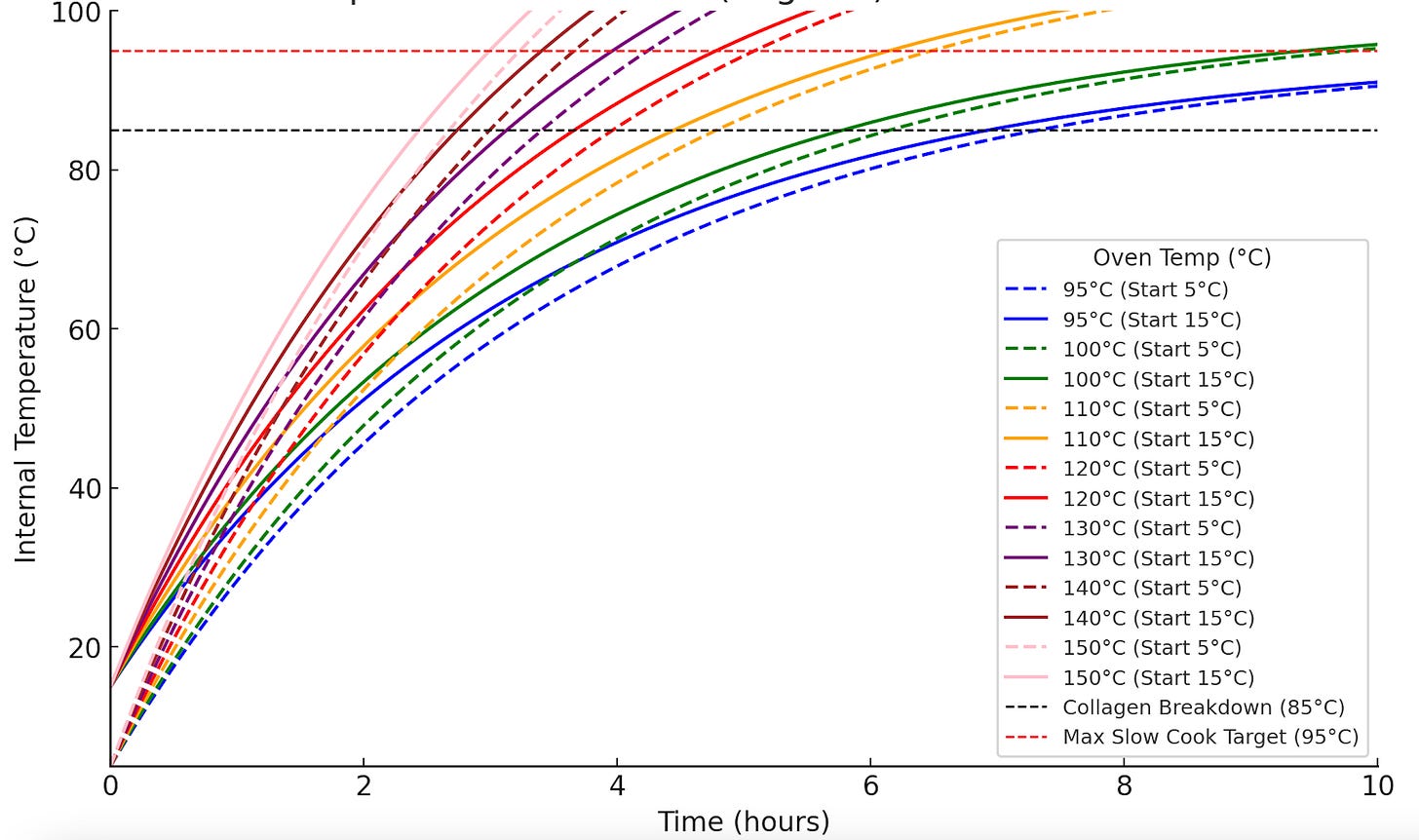

On bringing the lamb up to room temperature before cooking, I have amended my graph to show the predicted difference in cooking times based off the average fridge temp of 5°C and room temp of 15°C. We can take from it that the difference in cooking time is negligible, and much shorter than the actual time it would take to even bring the lamb up to room temp. Considering how long you’ll be cooking the lamb for and how gently you’ll be heating it, it will have plenty of time to relax in the oven.

On resting the lamb after cooking - do not skip this step! It’s not unique to slow cooking or to lamb. Resting is your friend. Really cold or really hot results in the muscles being tight, which limits its liquid-holding capacity. Allowing it to rest for at least 30 minutes gives time for the muscles to relax and loosen, and for that juicy flavourful stock to be absorbed into the meat, instead of left in the pan.

- Dry vs. Wet

Lamb is around 75% water, so technically, you don’t need to add extra liquid. But I prefer to and would always suggest it. Why?

Moistness - It helps to prevent drying out.

Heat Transfer - Having a moist environment for the lamb to cook in encourages more even heat transfer (i.e. cooking) throughout the lamb.

GRAVY BABY! - You’re left with a super rich and fatty broth that, especially if you add some aromatics to the tray at the start, makes the BEST gravy without actually having to add anything else!

The practice of adding water actually brings up the third technique I also hear mentioned: braising. Braised lamb is a dish, but this wouldn’t be how to make it. The addition of water to the dish doesn’t make this a braising recipe, there are other cooking elements that would need to go into that. This is still just slow-cooked lamb.

Adding water really just aids the ‘foolproof’ aspect, as it adds yet another layer of security (on top of low temperature), to really prevent drying out and to slow down moisture loss.

- Covered vs. Uncovered

You can cook this uncovered. As we said before, lamb is 75% water, and you are cooking it at a very low temperature. Covering is, again, a way to negate any error. I would recommend it, it’s how I do it all the time. It sort of bolsters what the addition of water does, creating a homogenous environment for even collagen breakdown.

Like I said, don’t complicate it. Cover tightly with two layers of foil and live a life of peace.

- Seasoning

Lamb is my favourite meat. It has so much natural flavour! Therefore, I usually don't pre-season it very much. I tend to chuck some aromatics and herbs in, mainly because that’s what I grew up watching my mum do.

What I will say is absolutely non-negotiable, is salt.

When I first read Samin Nosrat’s ‘Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat’, salt was the only thing I wanted to talk about for months. It got to a point where an intervention was had (sad, I know). Different salt tastes different. This is very important. If you use a very strong salt in the recommended quantities, your lamb will taste like the sea (trust me, I’ve done it).

Now, the amount of salt you use is directly dependent on how early you salt it. You are best off salting your lamb 2 days before you want to cook it. It really isn’t the end of the world if you forget to do this, you just need to amend accordingly. I cannot express how much it is not worth cutting corners at this step. You cannot come back from it, I speak from experience (Test Kitchen gives deeper insights into this)!

Salt takes time to penetrate into the lamb. If you’re salting just before going in the oven, very little will penetrate through, leaving the salt on the outside and in the water (if using). You end up with a ruined broth and an overly salty outer layer, and a middle/centre with no salt seasoning at all. The more time you have to let the salt absorb, the deeper the salt will penetrate and the more evenly seasoned your lamb will be. Lamb is a very flavourful meat, so if you don’t have time, it will still taste great, just think - less marination time = less salt, and vice versa.

- Slits vs. No Slits

In the same way salt takes time to penetrate lamb, so does flavour enhancers like herbs, aromatics and other additions. A solution to this is to create slits and stuff your flavour enhancers into the lamb, speeding up the absorption process by increasing the contact surface area. 9 hours in the oven may seem like a long time, but it’s really not long enough for flavour additions to have a good chance at permeating through without some help.

Not making slits isn’t the end of the world. Most time, I just chuck everything in the dish. Since I use the double foil and water method, it creates a closed environment where the lamb essentially steams in flavoured water. Rubbing a split open garlic clove across the body of the lamb I find does the same job, and is much less tedious.

To read the full recipe with step by step explanations, subscribe to receive ‘TEST KITCHEN’ where we will also go over the comprehensive cheat sheet for this technique, temperatures, timings and science backed flavour pairings.

Happy eating and thanks for reading!

Fiona :)

Any questions, let me know below!